Being a trusted advisor means checking your ego at the door

Building resilience for the ups and downs of advisory relationships

I don't understand! I did all this great work, and I know what my stakeholders need to do. They just aren't listening to me.

No matter your data discipline, we all share a desire to see our work spur action. When our company is committed to data-driven decision making, we want the fruits of our work — the data-driven insights — to drive decision making! But it doesn't always pan out that way.

That's why I latched on when a UX Researcher in my LinkedIn network shared that she was reading The Trusted Advisor. The book's been around for a while, and although it's geared toward consultancies and other roles that connect to outside organizations (e.g., Sales and Customer Success), it's quite relevant within an organization as well. Data professionals are, in effect, data advisors to decision makers in their organization.

So I dove into the book with curiosity: How could I be more effective as a data advisor in my career? When presented with the authors' framework, what could I learn from how the trusted advisors in my life (professional, financial, healthcare) advise me?

Three tips to handle the bumps in advisory relationships

Being an advisor is tough. Even when you're confident about problem in abstract, or in a particular organization, you aren't guaranteed success in solving that problem in a new context, with new people, and new constraints. Like the opening quote, you may not see the traction you want at the speed you want it, if at all.

When talking about the characteristics of trusted advisors, the authors start by talking about ego: "Trusted advisors have a predilection to focus on the client, rather than themselves. They have enough ego strength to subordinate their own ego."

You may think this bit doesn't apply to you. I didn't, at first! My drive to be a data advisor stems from wanting to help others make the best decisions they can. Surely that's not egocentric!

The rough patches advisors hit in their advisory relationship are multifaceted, and the authors' framing revealed many places where one's ego can come into play. When you hit a rough patch in your advisory relationship, you might ask yourself:

How much of this rough patch is because I want validation that I'm right?

How much of this rough patch is because I want things to move faster? Maybe to help with recognition or a promotion.

How much of this rough patch is because I defined success as my stakeholder always / often taking my advice, and I want to be successful?

You can start to see where ego might creep in, despite the best of intentions. After reflecting on my own process, and what I learned from the book, I came away with three tips to improve my advisory relationships by reining in the ego.

Tip #1: Meet your stakeholder where they are

For data professionals, meeting stakeholders where they are is table stakes. Often, they won't have the depth of statistical or methodological understanding you do, and it's unreasonable to expect them to build that expertise. That's why you're there!

The authors take this a step further by defining four types of advisory relationships, and articulating success definitions in each. I've tweaked their success definitions to be more relevant to data teams and less focused on consultancy:

Service-Based: Focused on providing answers, expertise, and input through explanation. Success is when the above is timely and high quality.

Needs-Based: Focused on a business problem. Success is when the problem is resolved, no matter how simple, complex, or numerous the answers provided along the way.

Relationship-Based: Focus is across the organization, providing insights where they are relevant. Success looks like impacting business decisions based on work proposed by the advisor.

Trust-Based: Focus is on individual stakeholders throughout the organization. You're a safe haven to talk about hard issues, and advise on possible direction in the moment. Success looks like driving decision-making on the spot, without new work, based on your corpus of past analysis and insights.

Note the tension if you're building a data practice through a service-based relationship. Your stakeholders will consider you successful by providing high-quality answers to their questions. By definition, that success is defined on the short term, and centers the stakeholder as responsible for filling the team's backlog with future questions. Stakeholders can get busy, or have priorities change, and suddenly the requests may seem to dry up.

In order to build a team with long-term viability, you need to advance the advisory relationship with your stakeholders.

Tip #2: Listen intently to earn the right to explore ideas

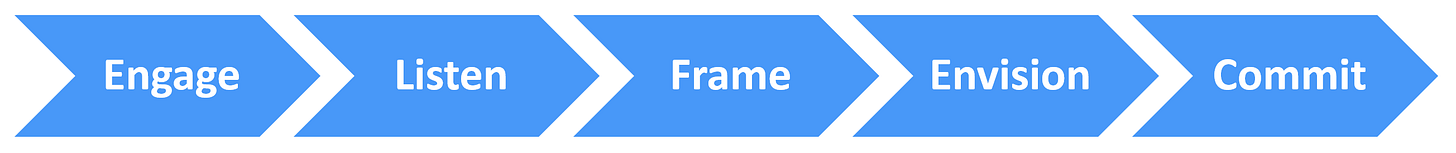

So how do you advance the advisory relationship? The second part of the book centers a 5-step process to do just that.

Elaborating on each step:

Engage: Establishing that there is an issue worth talking about, and the advisor is worth talking to about that issue.

Listen: Stakeholder is listened to about the issue at hand, and feels heard and understood.

Frame: Advisor and stakeholder work together to articulate one or more problem statement(s) related to the stakeholder's core issue.

Envision: Exploring possible solutions, and the realities that they would bring about. For example, if a company wanted to predict churn, a data team could deliver upstream indicator variables to watch, a dashboard that predicts churn quarter-by-quarter, or alerts that show up to each relevant stakeholder at the customer level. Each option creates a different future for the stakeholder, with different engagement expected: Which one has more appeal given what's feasible for the stakeholder team?

Commit: Advisor and stakeholder agree to a course of action, and the work begins.

Notably: We aren't defining the problem until step 3. The actual work isn't even included in this process -- we only get to commitment by the end of step 5! The authors repeat often that advisors have to "earn the right to engage in a mutual exploration of ideas."

This means, even as you're working on current projects, relationship building with your stakeholders is ongoing. And that engagement can't just be, "What projects do you have for me?" or "What questions do you want to answer?" The engagement should continually come back to the stakeholder's issue of the moment. Only some of those will be deemed relevant to your relationship (advance to Listen), and only some of those will lead to problem framing (advance to Frame). As with all funnels, you need a healthy inflow to ensure you have a reasonable outflow to work with.

Tip #3: Step out of productivity mode and inspect the moment

If there's a theme emerging in these tips, it's in the need to slow down. Cultivating stronger advisory relationships will take time. That can be hard if you're eager to see more impact, or be involved in more critical business discussions. It can be doubly hard in a high-stress environment: It's all about productivity and moving quickly! So let's just commit to a bunch of work right now!

I'll admit that I've been caught up in productivity waves often in my career. And when a ton of energy goes into a project, only for it to go nowhere... oof. It doesn't feel great. The knee-jerk reaction could be to push harder, or be upset, or blame the stakeholder who asked for the work but isn't taking action. (The authors would point out the presence of ego in these reactions.)

So the final tip continues the theme of slowing down: Step out of the productivity mode, push your ego to the side, and inspect the moment. If there's tension or lack of engagement in a relationship, it very likely has nothing to do with you or your work. Assuming that it does can cause the problem to escalate unnecessarily.

Instead, talk about it! "Originally, we talked about how this project might help your team with this problem you were having. I realize it's been a while since we've talked about how that problem is going, and I own that miss. How is this problem for you today? Have you found a workaround recently that we could discuss? Or has something else emerged that's more pressing?"

The authors call this approach naming and claiming: Detaching your ego from the situation, owning the tension, and opening conversation about it. It reminded me a great deal of a workshop I sat in a few months back on Relational Agility.1 In it, the facilitators discussed how to identify your emotions during those tense moments, and step out of the tension to address it head on.

Last Word: Knowing when enough is enough

The Trusted Advisor does a great job focusing on tips for the advisor to improve the relationship. But that isn't to say that the responsibility for the relationship is 100% on the advisor, or that all advisory relationships are healthy or viable. While they don't often talk about the responsibility of the advisees, early in the book the authors do share a noteworthy caveat:

No amount of interaction will add up to trust, if all your efforts are unilateral.

As advisors, where we draw the line of too much unilateral effort will vary. The book’s focus on the advisor’s action doesn’t mean that we can’t, or shouldn’t, draw that line. Instead, advisors need to continue building their resilience to new relationship challenges. Keep finding ways to nudge that line back. In doing so, you’ll find ways to take action, even when you have little or no control of the situation. Hopefully these tips will help you shift your own line back, if only a little bit.

Post photo by Pedro Sanz on Unsplash Nature | Resilience

While the current Relational Agility course has already wrapped up at the time of publishing, there are some great resources at the bottom of the workshop page.